Contents

Frantz Fanon Net Worth

How Much money Frantz Fanon has? For this question we spent 19 hours on research (Wikipedia, Youtube, we read books in libraries, etc) to review the post.

The main source of income: Authors

Total Net Worth at the moment 2024 year – is about $210,1 Million.

Youtube

Biography

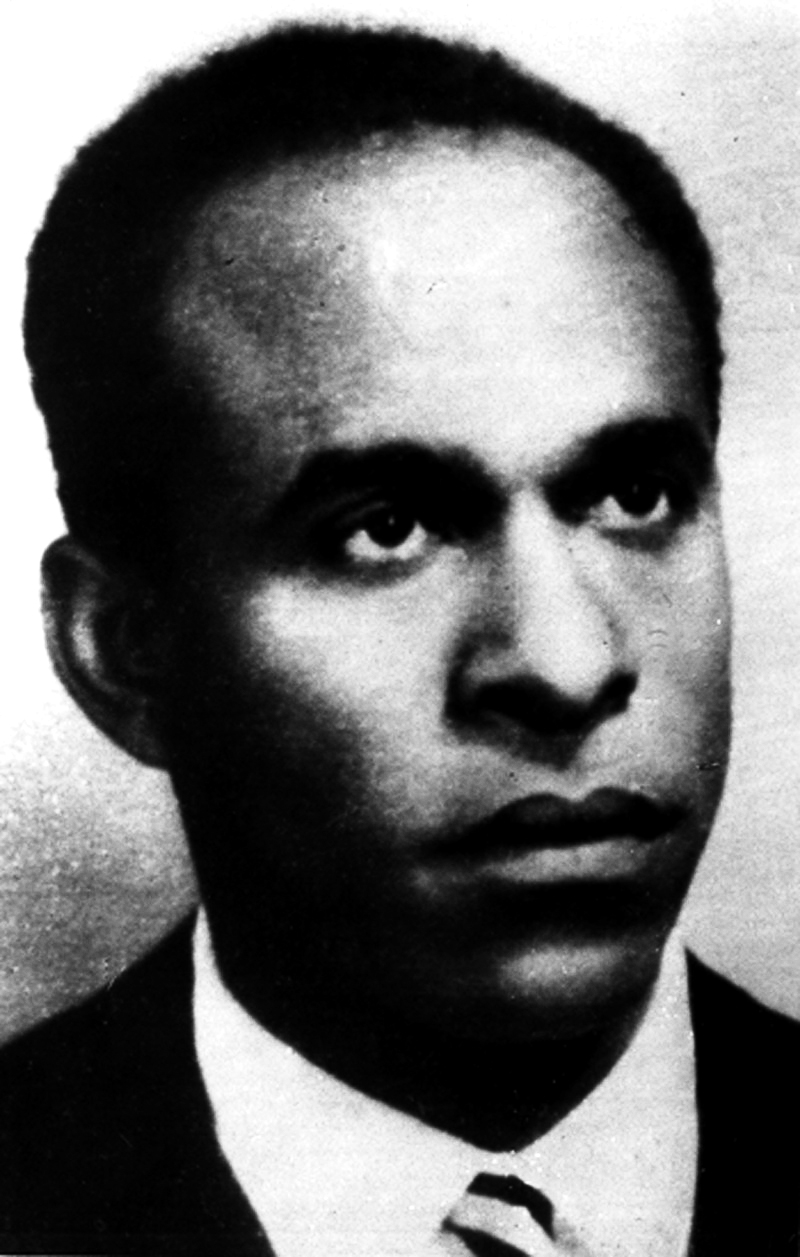

Frantz Fanon information Birth date: July 20, 1925 Death date: 1961-12-06 Birth place: Fort-de-France, Martinique, France Profession:Writer Spouse:Josie Fanon Children:Olivier Fanon, Mireille Fanon-Mend?s France

Height, Weight:

How tall is Frantz Fanon – 1,78m.

How much weight is Frantz Fanon – 62kg

Photos

Wiki

Biography,Early lifeFrantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which was then a French colony and is now a French departement. His father, Felix Casimir Fanon, was a descendant of enslaved Africans and indentured Indians and worked as a customs agent. His mother, Eleanore Medelice, was of black Martinician and white Alsatian descent and worked as a shopkeeper. Fanon was the youngest of four sons in a family of eight children, two of whom died in childhood. Fanons family was socio-economically middle-class. They could afford the fees for the Lycee Schoelcher, then the most prestigious high school in Martinique, where Fanon had the writer Aime Cesaire as one of his teachers.[11]Martinique and World War IIAfter France fell to the Nazis in 1940, Vichy French naval troops were blockaded on Martinique. Forced to remain on the island, French sailors took over the government from the Martiniquan people and established a collaborationist Vichy regime. In the face of economic distress and isolation under the blockade, they instituted an oppressive regime, Fanon described them as taking off their masks and behaving like authentic racists.[12] Residents made many complaints of harassment and sexual misconduct by the sailors. The abuse of the Martiniquan people by the French Navy influenced Fanon, reinforcing his feelings of alienation and his disgust with colonial racism. At the age of seventeen, Fanon fled the island as a dissident (the coined word for French West Indians joining Gaullist forces), traveling to British-controlled Dominica to join the Free French Forces.He enlisted in the Free French army and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. He was later transferred to an army base at Bejaia on the Kabylie coast of Algeria. Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France, notably in the battles of Alsace. In 1944 he was wounded at Colmar and received the Croix de guerre. When the Nazis were defeated and Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany along with photo journalists, Fanons regiment was bleached of all non-white soldiers. Fanon and his fellow Afro-Caribbean soldiers were sent to Toulon (Provence). Later, they were transferred to Normandy to await repatriation.During the war, Fanon was exposed to severe European anti-black racism. For example, white women liberated by black soldiers, often preferred to dance with fascist Italian prisoners, rather than fraternize with their liberators.In 1945, Fanon returned to Martinique. He lasted a short time there. He worked for the parliamentary campaign of his friend and mentor Aime Cesaire, who would be a major influence in his life. Cesaire ran on the communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique to the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Fanon stayed long enough to complete his baccalaureate and then went to France, where he studied medicine and psychiatry.Fanon was educated in Lyon, where he also studied literature, drama and philosophy, sometimes attending Merleau-Pontys lectures. During this period, he wrote three plays, of which two survive.[13] After qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Fanon did a residency in psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole under the radical Catalan psychiatrist Francois Tosquelles. He invigorated Fanons thinking by emphasizing the role of culture in psychopathology.After his residency, Fanon practised psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, for another year and then (from 1953) in Algeria. He was chef de service at the Blida–Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. He worked there until being deported in January 1957.[14]FranceIn France while completing his residency, Fanon wrote and published his first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), an analysis of the negative psychological effects of colonial subjugation upon Black people. Originally, the manuscript was the doctoral dissertation, submitted at Lyon, entitled Essay on the Disalienation of the Black, the rejection of the dissertation prompted Fanon to publish it as a book. For his doctor of philosophy degree, he submitted another dissertation of narrower scope and different subject. Left-wing philosopher Francis Jeanson, leader of the pro-Algerian independence Jeanson network, read Fanons manuscript and insisted upon the new title, he also wrote the epilogue. Jeanson was a senior book editor at Editions du Seuil, in Paris.[15]When Fanon submitted the manuscript of Black Skin, White Masks (1952) to Seuil, Jeanson invited him for an editor–author meeting, he said it did not go well as Fanon was nervous and over-sensitive. Despite Jeanson praising the manuscript, Fanon abruptly interrupted him, and asked: Not bad for a nigger, is it? Jeanson was insulted, became angry, and dismissed Fanon from his editorial office. Later, Jeanson said he learned that his response to Fanon’s discourtesy earned him the writers lifelong respect. Afterward, their working and personal relationship became much easier. Fanon agreed to Jeanson’s suggested title, Black Skin, White Masks.[15]AlgeriaThis section includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help to improve this section by introducing more precise citations. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)Fanon left France for Algeria, where he had been stationed for some time during the war. He secured an appointment as a psychiatrist at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. He radicalized his methods of treatment, particularly beginning socio-therapy to connect with his patients cultural backgrounds. He also trained nurses and interns. Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Liberation Nationale, after having made contact with Dr Pierre Chaulet at Blida in 1955.In The Wretched of the Earth (1961, Les damnes de la terre), published shortly before Fanons death, the writer defends the right of a colonized people to use violence to gain independence. In addition, he delineated the processes and forces leading to national independence or neocolonialism during the decolonization movement that engulfed much of the world after World War II. In defence of the use of violence by colonized peoples, Fanon argued that human beings who are not considered as such (by the colonizer) shall not be bound by principles that apply to humanity in their attitude towards the colonizer. His book was censored by the French government.Fanon made extensive trips across Algeria, mainly in the Kabyle region, to study the cultural and psychological life of Algerians. His lost study of The marabout of Si Slimane is an example. These trips were also a means for clandestine activities, notably in his visits to the ski resort of Chrea which hid an FLN base. By summer 1956 he wrote his Letter of resignation to the Resident Minister and made a clean break with his French assimilationist upbringing and education. He was expelled from Algeria in January 1957, and the nest of fellaghas [rebels] at Blida hospital was dismantled.Fanon left for France and travelled secretly to Tunis. He was part of the editorial collective of El Moudjahid, for which he wrote until the end of his life. He also served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government (GPRA). He attended conferences in Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, Leopoldville, Cairo and Tripoli. Many of his shorter writings from this period were collected posthumously in the book Toward the African Revolution. In this book Fanon reveals war tactical strategies, in one chapter he discusses how to open a southern front to the war and how to run the supply lines.[14]DeathUpon his return to Tunis, after his exhausting trip across the Sahara to open a Third Front, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. He went to the Soviet Union for treatment and experienced some remission of his illness. When he came back to Tunis once again, he dictated his testament The Wretched of the Earth. When he was not confined to his bed, he delivered lectures to Armee de Liberation Nationale (ALN) officers at Ghardimao on the Algero-Tunisian border. He made a final visit to Sartre in Rome. In 1961, the CIA arranged a trip to the U.S. for further leukemia treatment.[16]Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland, on 6 December 1961, under the name of Ibrahim Fanon, a Libyan nom de guerre that he had assumed in order to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front.[17] He was buried in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later, his body was moved to a martyrs (chouhada) graveyard at Ain Kerma in eastern Algeria. Frantz Fanon was survived by his French wife Josie (nee Duble), their son Olivier Fanon, and his daughter from a previous relationship, Mireille Fanon-Mendes France. Josie committed suicide in Algiers in 1989.[14] Mireille became a professor at Paris Descartes University and a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in international law and conflict resolution. She has also worked for UNESCO and the French National Assembly, and serves as president of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier married Valerie Fanon-Raspail, who manages the Fanon website.

Summary

Wikipedia Source: Frantz Fanon