Contents

Voltaire Net Worth

Voltaire how much money? For this question we spent 5 hours on research (Wikipedia, Youtube, we read books in libraries, etc) to review the post.

The main source of income: Authors

Total Net Worth at the moment 2024 year – is about $149,1 Million.

Youtube

Biography

Voltaire information Birth date: November 21, 1694 Death date: 1778-05-30 Birth place: Chick-fil-a, Compton, CA Profession:Writer Nationality:French

Height, Weight:

How tall is Voltaire – 1,66m.

How much weight is Voltaire – 60kg

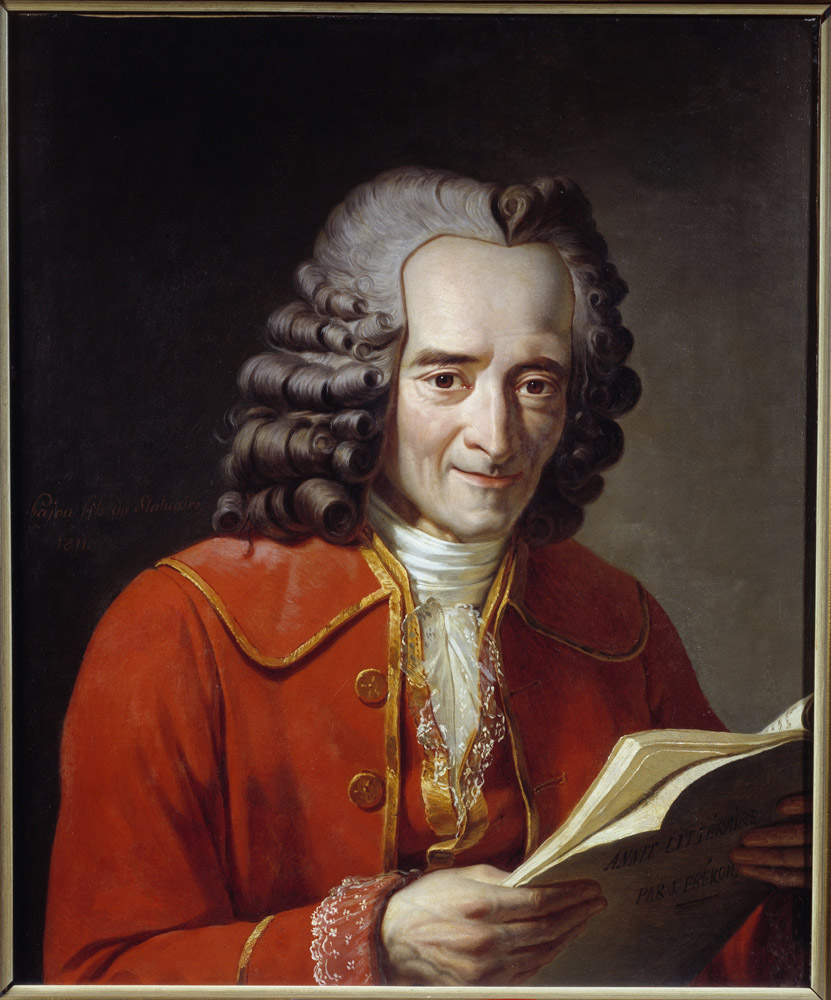

Photos

Wiki

Biography,Francois-Marie Arouet was born in Paris, the youngest of the five children of Francois Arouet (19 August 1649 – 1 January 1722), a lawyer who was a minor treasury official, and his wife, Marie Marguerite Daumard (c. 1660 – 13 July 1701), whose family was on the lowest rank of the French nobility. Some speculation surrounds Voltaires date of birth, because he claimed he was born on 20 February 1694 as the illegitimate son of a nobleman, Guerin de Rochebrune or Roquebrune. Two of his older brothers—Armand-Francois and Robert—died in infancy and his surviving brother, Armand, and sister Marguerite-Catherine were nine and seven years older, respectively. Nicknamed Zozo by his family, Voltaire was baptized on 22 November 1694, with Francois de Castagnere, abbe de Chateauneuf, and Marie Daumard, the wife of his mothers cousin, standing as godparents. He was educated by the Jesuits at the College Louis-le-Grand (1704–1711), where he was taught Latin, theology, and rhetoric, later in life he became fluent in Italian, Spanish, and English.By the time he left school, Voltaire had decided he wanted to be a writer, against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to become a lawyer. Voltaire, pretending to work in Paris as an assistant to a notary, spent much of his time writing poetry. When his father found out, he sent Voltaire to study law, this time in Caen, Normandy. Nevertheless, he continued to write, producing essays and historical studies. Voltaires wit made him popular among some of the aristocratic families with whom he mixed. In 1713, his father obtained a job for him as a secretary to the new French ambassador in the Netherlands, the marquis de Chateauneuf, the brother of Voltaires godfather. At The Hague, Voltaire fell in love with a French Protestant refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer (known as Pimpette). Their scandalous affair was discovered by de Chateauneuf and Voltaire was forced to return to France by the end of the year.Voltaire was imprisoned in the Bastille from 16 May 1717 to 15 April 1718 in a windowless cell with ten-foot thick walls.[11]Most of Voltaires early life revolved around Paris. From early on, Voltaire had trouble with the authorities for critiques of the government. These activities were to result in two imprisonments and a temporary exile to England. One satirical verse, in which Voltaire accused the Regent of incest with his own daughter, led to an eleven-month imprisonment in the Bastille.[12] The Comedie-Francaise had agreed in January 1717 to stage his debut play, ?dipe, and it opened in mid-November 1718, seven months after his release.[13] Its immediate critical and financial success established his reputation.[14] Both the Regent and King George I of Great Britain presented Voltaire with medals as a mark of their appreciation.[15]He mainly argued for religious tolerance and freedom of thought. He campaigned to eradicate priestly and aristo-monarchical authority, and supported a constitutional monarchy that protects peoples rights.[16][17]Adopts the name VoltaireThe author adopted the name Voltaire in 1718, following his incarceration at the Bastille. Its origin is unclear. It is an anagram of AROVET LI, the Latinized spelling of his surname, Arouet, and the initial letters of le jeune (the young).[18] According to a family tradition among the descendants of his sister, he was known as le petit volontaire (determined little thing) as a child, and he resurrected a variant of the name in his adult life.[19] The name also reverses the syllables of Airvault, his familys home town in the Poitou region.[20]Richard Holmes[21] supports the anagrammatic derivation of the name, but adds that a writer such as Voltaire would have intended it to also convey its connotations of speed and daring. These come from associations with words such as voltige (acrobatics on a trapeze or horse), volte-face (a spinning about to face ones enemies), and volatile (originally, any winged creature). Arouet was not a noble name fit for his growing reputation, especially given that names resonance with a rouer (to be beaten up) and roue (a debauche).In a letter to Jean-Baptiste Rousseau in March 1719, Voltaire concludes by asking that, if Rousseau wishes to send him a return letter, he do so by addressing it to Monsieur de Voltaire. A postscript explains: Jai ete si malheureux sous le nom dArouet que jen ai pris un autre surtout pour netre plus confondu avec le poete Roi, (I was so unhappy under the name of Arouet that I have taken another, primarily so as to cease to be confused with the poet Roi.)[22] This probably refers to Adenes le Roi, and the oi diphthong was then pronounced like modern ouai, so the similarity to Arouet is clear, and thus, it could well have been part of his rationale. Indeed, Voltaire is known also to have used at least 178 separate pen names during his lifetime.[23]La Henriade and MariamneVoltaires next play Artemire, set in ancient Macedonia, opened on 15 February 1720. It was a flop and only fragments of the text survive.[24] He instead turned to an epic poem about Henri IV of France that he had begun in early 1717.[25] Denied a licence to publish, in August 1722 Voltaire headed north to find a publisher outside France. On the journey, he was accompanied by his mistress, Marie-Marguerite de Rupelmonde, a young widow.[26]At Brussels, Voltaire and Rousseau met up for a few days, before Voltaire and his mistress continued northwards. A publisher was eventually secured in The Hague.[27] In the Netherlands, Voltaire was struck and impressed by the openness and tolerance of Dutch society.[28] On his return to France, he secured a second publisher in Rouen, who agreed to publish La Henriade clandestinely.[29] After Voltaires recovery from a month-long smallpox infection in November 1723, the first copies were smuggled into Paris and distributed.[30] While the poem was an instant success, Voltaires new play, Mariamne, was a failure when it first opened in March 1724.[31] Heavily reworked, it opened at the Comedie-Francaise in April 1725 to a much-improved reception.[31] It was among the entertainments provided at the wedding of Louis XV and Marie Leszczynska in September 1725.[31]Great BritainIn early 1726, a young French nobleman, the chevalier de Rohan-Chabot, taunted Voltaire about his change of name, and Voltaire retorted that his name would be honoured while de Rohan would dishonour his.[32] Infuriated, de Rohan arranged for Voltaire to be beaten up by thugs a few days later.[33] Seeking compensation, redress, or revenge, Voltaire challenged de Rohan to a duel, but the aristocratic de Rohan family arranged for Voltaire to be arrested and imprisoned in the Bastille on 17 April 1726 without a trial or an opportunity to defend himself.[34][35] Fearing an indefinite prison sentence, Voltaire suggested that he be exiled to England as an alternative punishment, which the French authorities accepted.[36] On 2 May, he was escorted from the Bastille to Calais, where he was to embark for Britain.[37]In England, Voltaire lived largely in Wandsworth, with acquaintances including Everard Fawkener.[38] From December 1727 to June 1728 he lodged at Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, now commemorated by a plaque, to be nearer to his British publisher.[39] Voltaire circulated throughout English high society, meeting Alexander Pope, John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and many other members of the nobility and royalty.[40] Voltaires exile in Great Britain greatly influenced his thinking. He was intrigued by Britains constitutional monarchy in contrast to French absolutism, and by the countrys greater support of the freedoms of speech and religion.[41] He was influenced by the writers of the age, and developed an interest in earlier English literature, especially the works of Shakespeare, still relatively unknown in continental Europe.[42] Despite pointing out his deviations from neoclassical standards, Voltaire saw Shakespeare as an example that French writers might emulate, since French drama, despite being more polished, lacked on-stage action. Later, however, as Shakespeares influence began growing in France, Voltaire tried to set a contrary example with his own plays, decrying what he considered Shakespeares barbarities. Voltaire may have been present at the funeral of Isaac Newton,[43] and met Newtons niece, Catherine Conduitt.[39] In 1727 he published two essays in English, Upon the Civil Wars of France, Extracted from Curious Manuscripts, and Upon Epic Poetry of the European Nations, from Homer Down to Milton.[39]Pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1735After two and a half years in exile, Voltaire returned to France, and after a few months living in Dieppe, the authorities permitted him to return to Paris.[44] At a dinner, French mathematician Charles Marie de La Condamine proposed buying up the lottery that was organized by the French government to pay off its debts, and Voltaire joined the consortium, earning perhaps a million livres.[45] He invested the money cleverly and on this basis managed to convince the Court of Finances that he was of good conduct and so was able to take control of a capital inheritance from his father that had hitherto been tied up in trust. He was now indisputably rich.[46][47]Further success followed, in 1732, with his play Zaire, which when published in 1733 carried a dedication to Fawkener that praised English liberty and commerce.[48] At this time he published his views on British attitudes toward government, literature, religion and science in a collection of essays in letter form entitled Letters Concerning the English Nation (London, 1733).[49] In 1734, they were published in French as Lettres philosophiques in Rouen.[50][note 1] Because the publisher released the book without the approval of the royal censor and Voltaire regarded the British constitutional monarchy as more developed and more respectful of human rights (particularly religious tolerance) than its French counterpart, the French publication of Letters caused a huge scandal, the book was publicly burnt and banned, and Voltaire was forced again to flee Paris.[16]Chateau de CireyIn the frontispiece to Voltaires book on Newtons philosophy, Emilie du Chatelet appears as Voltaires muse, reflecting Newtons heavenly insights down to Voltaire.[51]In 1733, Voltaire met Emilie du Chatelet, a married mother of three who was 12 years his junior and with whom he was to have an affair for 16 years.[52] To avoid arrest after the publication of Letters, Voltaire took refuge at her husbands chateau at Cirey-sur-Blaise, on the borders of Champagne and Lorraine.[53] Voltaire paid for the buildings renovation,[54] and Emilies husband, the Marquis du Chatelet, sometimes stayed at the chateau with his wife and her lover.[55] The relationship had a significant intellectual element. Voltaire and the Marquise collected over 21,000 books, an enormous number for the time.[citation needed] Together, they studied these books and performed experiments in the natural sciences at Cirey, which included an attempt to determine the nature of fire.[56]Having learned from his previous brushes with the authorities, Voltaire began his habit of keeping out of personal harms way and denying any awkward responsibility. He continued to write plays, such as Merope (or La Merope francaise) and began his long research into science and history. Again, a main source of inspiration for Voltaire were the years of his British exile, during which he had been strongly influenced by the works of Sir Isaac Newton. Voltaire strongly believed in Newtons theories, he performed experiments in optics at Cirey,[57] and was one of the sources for the famous story of Newton and the apple falling from the tree, which he had learned from Newtons niece in London and first mentioned in his Letters.[39]In the fall of 1735, Voltaire was visited by Francesco Algarotti, who was preparing a book about Newton in Italian.[58] Partly inspired by the visit, the Marquise translated Newtons Latin Principia into French in full, and it remained the definitive French translation into the 21st century.[16] Both she and Voltaire were also curious about the philosophies of Gottfried Leibniz, a contemporary and rival of Newton. While Voltaire remained a firm Newtonian, the Marquise adopted certain aspects of Leibnizs arguments against Newton.[16][59] Voltaires own book Elements de la philosophie de Newton (Elements of Newtons Philosophy) made Newton accessible and understandable to a far greater public, and the Marquise wrote a celebratory review in the Journal des savants.[16][60] Voltaires work was instrumental in bringing about general acceptance of Newtons optical and gravitational theories in France.[16][61]Voltaire and the Marquise also studied history, particularly those persons who had contributed to civilization. Voltaires second essay in English had been Essay upon the Civil Wars in France. It was followed by La Henriade, an epic poem on the French King Henri IV, glorifying his attempt to end the Catholic-Protestant massacres with the Edict of Nantes, and by a historical novel on King Charles XII of Sweden. These, along with his Letters on the English mark the beginning of Voltaires open criticism of intolerance and established religions.[citation needed] Voltaire and the Marquise also explored philosophy, particularly metaphysics, the branch of philosophy that deals with being and with what lies beyond the material realm, such as whether or not there is a God and whether people have souls. Voltaire and the Marquise analysed the Bible and concluded that much of its content was dubious.[62] Voltaires critical views on religion are reflected in his belief in separation of church and state and religious freedom, ideas that he had formed after his stay in England.In August 1736, Frederick the Great, then Crown Prince of Prussia and a great admirer of Voltaire, initiated a correspondence with him.[63] That December, Voltaire moved to Holland for two months and became acquainted with the scientists Herman Boerhaave and s Gravesande.[64] From mid-1739 to mid-1740 Voltaire lived largely in Brussels, at first with the Marquise, who was unsuccessfully attempting to pursue a 60-year-old family legal case regarding the ownership of two estates in Limburg.[65] In July 1740, he traveled to the Hague on behalf of Frederick in an attempt to dissuade a dubious publisher, van Duren, from printing without permission Fredericks Anti-Machiavel.[66] In September Voltaire and Frederick met for the first time in Moyland Castle near Cleves and in November Voltaire was Fredericks guest in Berlin for two weeks,[67] in September 1742 they met in Aix-la-Chapelle.[68] Voltaire was sent to Fredericks court in 1743 by the French government as an envoy and spy to gauge Fredericks military intentions in the War of the Austrian Succession.[69]Die Tafelrunde by Adolph von Menzel. Guests of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci, including members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Voltaire (third from left)Though deeply committed to the Marquise, Voltaire by 1744 found life at the chateau confining. On a visit to Paris that year, he found a new love—his niece. At first, his attraction to Marie Louise Mignot was clearly sexual, as evidenced by his letters to her (only discovered in 1957).[70][71] Much later, they lived together, perhaps platonically, and remained together until Voltaires death. Meanwhile, the Marquise also took a lover, the Marquis de Saint-Lambert.[72]PrussiaAfter the death of the Marquise in childbirth in September 1749, Voltaire briefly returned to Paris and in mid-1750 moved to Prussia to the court of Frederick the Great.[73] The Prussian king (with the permission of Louis XV) made him a chamberlain in his household, appointed him to the Order of Merit, and gave him a salary of 20,000 French livres a year.[74] He had rooms at Sanssouci and Charlottenburg Palace.[75] Though life went well at first[76]—in 1751 he completed Micromegas, a piece of science fiction involving ambassadors from another planet witnessing the follies of humankind[77]—his relationship with Frederick the Great began to deteriorate after he was accused of theft and forgery by a Jewish financier, Abraham Hirschel, who had invested in Saxon government bonds, on behalf of Voltaire, at a time when Frederick was involved in sensitive diplomatic negotiations with Saxony.[78]He encountered other difficulties: an argument with Maupertuis, the president of the Berlin Academy of Science and a former rival for Emilies affections, provoked Voltaires Diatribe du docteur Akakia (Diatribe of Doctor Akakia), which satirized some of Maupertuiss theories and his abuse of power in his persecutions of a mutual acquaintance, Johann Samuel Konig. This greatly angered Frederick, who ordered all copies of the document burned.[79] On 1 January 1752, Voltaire offered to resign as chamberlain and return his insignia of the Order of Merit, at first, Frederick refused until eventually permitting Voltaire to leave in March.[80] On a slow journey back to France, Voltaire stayed at Leipzig and Gotha for a month each, and Kassel for two weeks, arriving at Frankfurt on 31 May. The following morning, he was detained at the inn where he was staying by Fredericks agents, who held him in the city for over three weeks while they, Voltaire and Frederick argued by letter over the return of a book of poetry. Marie Louise joined him on 9 June. She and her uncle only left Frankfurt in July after she had defended herself from the unwanted advances of one of Fredericks agents and Voltaires luggage had been ransacked and valuable items taken by the agents.[81]Voltaires attempts to vilify Frederick for his agents actions at Frankfurt were largely unsuccessful. Voltaire responded by composing Memoires pour Servir a la Vie de M. de Voltaire, a work published after his death that paints a largely negative picture of his time spent with Frederick. However, the correspondence between them continued, and though they never met in person again, after the Seven Years War they largely reconciled.[82]Geneva and FerneyVoltaires chateau at Ferney, FranceVoltaires slow progress toward Paris continued through Mainz, Mannheim, Strasbourg, and Colmar,[83] but in January 1754 Louis XV banned him from Paris,[84] so instead he turned for Geneva, near which he bought a large estate (Les Delices) in early 1755.[85] Though he was received openly at first, the law in Geneva, which banned theatrical performances, and the publication of The Maid of Orleans against his will soured his relationship with Calvinist Genevans.[86] In late 1758, he bought an even larger estate at Ferney, on the French side of the Franco-Swiss border.[87] Early the following year, Voltaire completed and published Candide, ou lOptimisme (Candide, or Optimism). This satire on Leibnizs philosophy of optimistic determinism remains the work for which Voltaire is perhaps best known. He would stay in Ferney for most of the remaining 20 years of his life, frequently entertaining distinguished guests, such as James Boswell, Adam Smith, Giacomo Casanova, and Edward Gibbon.[88] In 1764, he published one of his best-known philosophical works, the Dictionnaire philosophique, a series of articles mainly on Christian history and dogmas, a few of which were originally written in Berlin.[35]From 1762, he began to champion unjustly persecuted people, the case of Huguenot merchant Jean Calas being the most celebrated.[35] He had been tortured to death in 1763, supposedly because he had murdered his eldest son for wanting to convert to Catholicism. His possessions were confiscated and his two daughters were taken from his widow and were forced into Catholic convents. Voltaire, seeing this as a clear case of religious persecution, managed to overturn the conviction in 1765.[89]Voltaire was initiated into Freemasonry the month before his death. On 4 April 1778 Voltaire accompanied his close friend Benjamin Franklin into La Loge des Neuf S?urs or Les Neuf S?urs in Paris, France and became an Entered Apprentice Freemason. Benjamin Franklin … urged Voltaire to become a freemason, and Voltaire agreed, perhaps only to please Franklin.[90][91][92]Death and burialIn February 1778, Voltaire returned for the first time in over 25 years to Paris, among other reasons to see the opening of his latest tragedy, Irene.[93] The five-day journey was too much for the 83-year-old, and he believed he was about to die on 28 February, writing I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition. However, he recovered, and in March saw a performance of Irene, where he was treated by the audience as a returning hero.[35]House in Paris where Voltaire diedHe soon became ill again and died on 30 May 1778. The accounts of his deathbed have been numerous and varying, and it has not been possible to establish the details of what precisely occurred. His enemies related that he repented and accepted the last rites given by a Catholic priest, or that he died under great torment, while his adherents told how he was defiant to his last breath.[94] According to one story, his last words were, Now is not the time for making new enemies. It was his response to a priest at the side of his deathbed, asking Voltaire to renounce Satan.[95] However, this appears to have originated from a joke first published in a Massachusetts newspaper in 1856, and was only attributed to Voltaire in the 1970s.[96]Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial in Paris,[97] but friends and relations managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellieres in Champagne, where Marie Louises brother was abbe.[98] His heart and brain were embalmed separately.[99]Voltaires tomb in Pariss PantheonOn 11 July 1791, he was enshrined in the Pantheon, after the National Assembly of France, which regarded him as a forerunner of the French Revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris.[100] It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that Andre Gretry had composed specially for the event, which included a part for the tuba curva (an instrument that originated in Roman times as the cornu but had recently been revived under a new name[101]).

Summary

Wikipedia Source: Voltaire