Contents

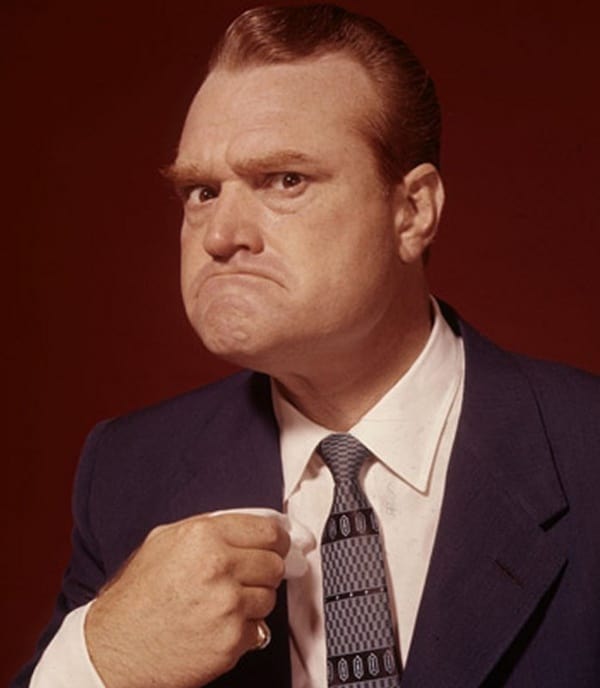

Red Skelton Net Worth

How rich is Red Skelton? For this question we spent 16 hours on research (Wikipedia, Youtube, we read books in libraries, etc) to review the post.

The main source of income: Authors

Total Net Worth at the moment 2024 year – is about $77,9 Million.

Youtube

Biography

Red Skelton information Birth date: July 18, 1913 Death date: 1997-09-17 Birth place: Vincennes, Indiana, United States Height:6 2 (1.88 m) Profession:Writer, Producer, Actor Spouse:Edna Marie Stillwell (divorced), Georgia Davis (divorced), Lothian Tolandhis death Children:* Valentina Marie, * Richard Freeman, Valentina Richard Freeman

Height, Weight:

How tall is Red Skelton – 1,72m.

How much weight is Red Skelton – 72kg

Pictures

Wiki

Biography,Early years, the medicine show and the circus (1913–29)Born on July 18, 1913, in Vincennes, Indiana, Richard Skelton was the fourth and youngest son of Ida Mae (nee Fields) and Joseph Elmer Skelton. Joseph, a grocer, died two months before Richard was born, he had once been a clown with the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus. During Skeltons lifetime there was some dispute about the year of his birth. Author Wesley Hyatt suggests that since he began working at such an early age, Skelton may have claimed he was older than he actually was in order to gain employment.[a][b] Vincennes neighbors described the Skelton family as being extremely poor, a childhood friend remembered that her parents broke up a youthful romance between her sister and Skelton because they thought he had no future.Because of the loss of his father, Skelton went to work as early as the age of seven, selling newspapers and doing other odd jobs to help his family, who had lost the family store and their home. He quickly learned the newsboys patter and would keep it up until a prospective buyer bought a copy of the paper just to quiet him. According to later accounts, Skeltons early interest in becoming an entertainer stemmed from an incident that took place in Vincennes around 1923, when a stranger, supposedly the comedian Ed Wynn, approached Skelton, who was the newsboy selling papers outside a Vincennes theater. When the man asked Skelton what events were going on in town, Skelton suggested he see the new show in town. The man purchased every paper Skelton had, providing enough money for the boy to purchase a ticket for himself. The stranger turned out to be one of the shows stars, who later took the boy backstage to introduce him to the other performers. The experience prompted Skelton, who had already shown comedic tendencies, to pursue a career as a performer.[c]Skelton discovered at an early age that he could make people laugh. Skelton dropped out of school around 1926 or 1927, when he was 13 or 14 years old, but he already had some experience performing in minstrel shows in Vincennes, and on a showboat, The Cotton Blossom, that plied the Ohio and Missouri rivers. He enjoyed his work on the riverboat, moving on only after he realized that showboat entertainment was coming to an end. Skelton, who was interested in all forms of acting, took a dramatic role with the John Lawrence stock theater company, but was unable to deliver his lines in a serious manner, the audience laughed instead. In another incident, while performing in Uncle Toms Cabin, Skelton was on an unseen treadmill, when it malfunctioned and began working in reverse, the frightened young actor called out, Help! Im backing into heaven! He was fired before completing a weeks work in the role.[11] At the age of 15, Skelton did some early work on the burlesque circuit,[12] and reportedly spent four months with the Heganbeck-Wallace Circus in 1929, when he was 16 years old.[13]Ida Skelton, who held multiple jobs to support her family after the death of her husband, did not suggest that her youngest son had run away from home to become an entertainer, but his destiny had caught up with him at an early age. She let him go with her blessing. Times were tough during the Great Depression, and it may have meant one less child for her to feed.[14] Around 1929, while Skelton was still a teen, he joined Doc R.E. Lewiss traveling medicine show as an errand boy who sold bottles of medicine to the audience. During one show, when Skelton accidentally fell from the stage, breaking several bottles of medicine as he fell, people laughed. Both Lewis and Skelton realized one could earn a living with this ability and the fall was worked into the show. He also told jokes and sang in the medicine show during his four years there.[15] Skelton earned ten dollars a week, and sent all of it home to his mother. When she worried that he was keeping nothing for his own needs, Skelton reassured her: We get plenty to eat, and we sleep in the wagon.[16]Burlesque to vaudeville (1929–37)Red and Edna Skelton at home, 1942As burlesque comedy material became progressively more ribald, Skelton moved on. He insisted that he was no prude, I just didnt think the lines were funny. He became a sought-after master of ceremonies for dance marathons (known as walkathons at the time), a popular fad in the 1930s.[17] The winner of one of the marathons was Edna Stillwell, an usher at the old Pantages Theater.[18][19][d] She approached Skelton after winning the contest and told him that she did not like his jokes, he asked if she could do better.[23] They married in 1931 in Kansas City, and Edna began writing his material. At the time of their marriage Skelton was one month away from his 18th birthday, Edna was 16.[24] When they learned that Skeltons salary was to be cut, Edna went to see the boss, he resented the interference, until she came away with not only a raise, but additional considerations as well. Since he had left school at an early age, his wife bought textbooks and taught him what he had missed. With Ednas help, Skelton received a high school equivalency degree.[23][e]The couple put together an act and began booking it at small midwestern theaters.[26] When an offer came for an engagement in Harwich Port, Massachusetts, some 2,000 miles from Kansas City, they were pleased to get it because of its proximity to their ultimate goal, the vaudeville houses of New York City. To get to Massachusetts they bought a used car and borrowed five dollars from Ednas mother, but by the time they arrived in St. Louis they had only fifty cents. Skelton asked Edna to collect empty cigarette packs, she thought he was joking, but did as he asked. He then spent their fifty cents on bars of soap, which they cut into small cubes and wrapped with the tinfoil from the cigarette packs. By selling their products for fifty cents each as fog remover for eyeglasses, the Skeltons were able to afford a hotel room every night as they worked their way to Harwich Port.[16]Doughnut DunkersSkelton with John Garfield at the 1944 FDR Birthday BallSkelton and Edna worked for a year in Camden, New Jersey, and were able to get an engagement at Montreals Lido Club in 1934 through a friend who managed the chorus lines at New Yorks Roxy Theatre.[16] Despite an initial rocky start, the act was a success, and brought them more theater dates throughout Canada.[f]Skeltons performances in Canada lead to new opportunities and the inspiration for a new, innovative routine that brought him recognition in the years to come. While performing in Montreal, the Skeltons met Harry Anger, a vaudeville producer for New York Citys Loews State Theatre. Anger promised the pair a booking as a headlining act at Loews, but they would need to come up with new material for the engagement. While the Skeltons were having breakfast in a Montreal diner, Edna had an idea for a new routine as she and Skelton observed the other patrons eating doughnuts and drinking coffee. They devised the Doughnut Dunkers routine, with Skeltons visual impressions of how different people ate doughnuts.[g] The skit won them the Loews State engagement and a handsome fee.[26][29]The couple viewed the Loews State engagement in 1937 as Skeltons big chance. They hired New York comedy writers to prepare material for the engagement, believing they needed more sophisticated jokes and skits than the routines Skelton normally performed. However, his New York audience did not laugh or applaud until Skelton abandoned the newly written material and began performing the Doughnut Dunkers and his older routines.[h] The doughnut-dunking routine also helped Skelton rise to celebrity status. In 1937, while he was entertaining at the Capitol Theater in Washington, D.C., President Franklin D. Roosevelt invited Skelton to perform at a White House luncheon. During one of the official toasts, Skelton grabbed Roosevelts glass, saying, Careful what you drink, Mr. President. I got rolled in a place like this once. His humor appealed to FDR and Skelton became the master of ceremonies for Roosevelts official birthday celebration for many years afterward.[30]Film workSkelton with Ann Rutherford and Virginia Grey as radio detective The Fox in Whistling in the Dark (1941)Skeltons first contact with Hollywood came in the form of a failed 1932 screen test. In 1938 he made his film debut for RKO Pictures in the supporting role of a camp counselor in Having Wonderful Time.[31] He appeared in two short subjects for Vitaphone in 1939: Seeing Red and The Broadway Buckaroo.[32] Actor Mickey Rooney contacted Skelton, urging him to try for work in films after seeing him perform his Doughnut Dunkers act at President Roosevelts 1940 birthday party.[33][34] For his MGM screen test, Skelton performed many of his more popular skits, such as Guzzlers Gin, but added some impromptu pantomimes as the cameras were rolling. Imitation of Movie Heroes Dying were Skeltons impressions of the cinema deaths of stars like George Raft, Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney.[30][35]Skelton began appearing in numerous films for MGM. In 1940 he provided comic relief as a lieutenant in Frank Borzages war drama Flight Command, opposite Robert Taylor, Ruth Hussey and Walter Pidgeon.[36] In 1941 he also provided comic relief in Harold S. Bucquets Dr. Kildare medical dramas, Dr. Kildares Wedding Day and The People vs. Dr. Kildare. Skelton was soon starring in comedy features as inept radio detective The Fox, the first of which was Whistling in the Dark (1941) in which he began working with director S. Sylvan Simon, who would become his favorite director.[37] He reprised the same role opposite Ann Rutherford in Simons other pictures, including Whistling in Dixie (1942) and Whistling in Brooklyn (1943).[38][39][40] In 1941, Skelton began appearing in musical comedies, starring opposite Eleanor Powell, Ann Sothern and Robert Young in Norman Z. McLeods Lady Be Good.[41] In 1942 Skelton again starred opposite Eleanor Powell in Edward Buzzells Ship Ahoy, and alongside Ann Sothern in McLeods Panama Hattie.[42]Skelton (center left) in Panama Hattie (1942)In 1943, after a memorable role as a nightclub hatcheck attendant who becomes King Louis XV of France in a dream opposite Lucille Ball and Gene Kelly in Roy Del Ruths Du Barry Was a Lady,[43][44] Skelton starred as Joseph Rivington Reynolds, a hotel valet besotted with Broadway starlet Constance Shaw (Powell) in Vincente Minnellis romantic musical comedy, I Dood It. The film was largely a remake of Buster Keatons Spite Marriage, Keaton, who had become a comedy consultant to MGM after his film career had diminished, began coaching Skelton on set during the filming. Keaton worked in this capacity on several of Skeltons films, and his 1926 film The General was also later rewritten to become Skeltons A Southern Yankee (1948), under directors S. Silvan Simon and Edward Sedgwick.[45][46][47] Keaton was convinced enough of Skeltons comedic talent that he approached MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer with a request to create a small company within MGM for himself and Skelton, where the two could work on film projects. Keaton offered to forgo his salary if the films made by the company were not box office hits, Mayer chose to decline the request.[48] In 1944, Skelton starred opposite Esther Williams in George Sidneys musical comedy Bathing Beauty, playing a songwriter with romantic difficulties. He next had a relatively minor role as a TV announcer who, in the course of demonstrating a brand of gin, progresses from mild inebriation through messy drunkenness to full-blown stupor in the When Television Comes segment of Ziegfeld Follies, which featured William Powell and Judy Garland in the main roles.[49] In 1946, Skelton played boastful clerk J. Aubrey Piper opposite Marilyn Maxwell and Marjorie Main in Harry Beaumonts comedy picture The Show-Off.[50]Skeltons imprint ceremony at Graumans Chinese Theatre, June 18, 1942.[51] His wife, Edna, is on his left. Skelton also imprinted Juniors shoes along with the message, We Dood It!. Theater owner Sid Grauman is in foreground of photo.Skeltons contract called for MGMs approval prior to his radio shows and other appearances.[52] When he renegotiated his long-term contract with MGM, he wanted a clause that permitted him to remain working in radio and to be able to work on television, which was then largely experimental. At the time, the major work in the medium was centered in New York, Skelton had worked there for some time and was able to determine that he would find success with his physical comedy through the medium.[36][i] By 1947, Skeltons work interests were focused not on films, but on radio and television. His MGM contract was rigid enough to require the studios written consent for his weekly radio shows, as well as any benefit or similar appearances he made, radio offered less restrictions, more creative control and a higher salary.[52][54] Skelton asked for a release from MGM after learning he could not raise the $750,000 needed to buy out the remainder of his contract.[52] He also voiced frustration with the film scripts he was offered while on the set of The Fuller Brush Man, saying, Movies are not my field. Radio and television are.[55][j] He did not receive the desired television clause nor a release from his MGM contract.[58] In 1948, columnist Sheilah Graham printed that Skeltons wishes were to make only one film a year, spending the rest of the time traveling the U.S. with his radio show.[37]Skeltons ability to successfully ad-lib often meant that the way the script was written was not always the way it was recorded on film. Some directors were delighted with the creativity, but others were often frustrated by it.[k] S. Sylvan Simon, who became a close friend, allowed Skelton free rein when directing him.[60][61] MGM became annoyed with Simon during the filming of The Fuller Brush Man, as the studio contended that Skelton should have been playing romantic leads instead of performing slapstick. Simon and MGM parted company when he was not asked to direct retakes of Skeltons A Southern Yankee, Simon asked that his name be removed from the films credits.[47][62]Skelton was willing to negotiate with MGM to extend the agreement provided he would receive the right to pursue television. This time the studio was willing to grant it, making Skelton the only major MGM personality with the privilege. The 1950 negotiations allowed him to begin working in television beginning September 30, 1951.[63][64] During the last portion of his contract with the studio, Skelton was working in radio and on television in addition to films. He would go on to appear in films such as Jack Donohues The Yellow Cab Man (1950),[65] Roy Rowland and Buster Keatons Excuse My Dust (1951),[66] Charles Walters Texas Carnival (1951),[67] Mervyn LeRoys Lovely to Look At (1952),[36] Robert Z. Leonards The Clown (1953) and The Great Diamond Robbery (1954),[68] and Norman Z. McLeods poorly received Public Pigeon No. 1 (1957),[69] his last major film role, which originated incidentally from an episode of the television anthology series Climax!.[70] In a 1956 interview, he said he would never work simultaneously in all three media again.[71] As a result, Skelton would make only a couple of minor appearances in films after this, including playing a saloon drunk in Around the World in Eighty Days (1956), a gambler in Oceans 11 (1960), and a Neanderthal man in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965).[72]Radio, divorce and remarriage (1937–51)Performing the Doughnut Dunkers routine led to Skeltons first appearance on Rudy Vallees The Fleischmanns Yeast Hour on August 12, 1937. Vallees program had a talent show segment and those who were searching for stardom were eager to be heard on it. Vallee also booked veteran comic and fellow Indiana native Joe Cook to appear as a guest with Skelton. The two Hoosiers proceeded to trade jokes about their home towns, with Skelton contending to Cook, an Evansville native, that the city was a suburb of Vincennes. The show received enough fan mail after the performance to invite both comedians back two weeks after Skeltons initial appearance and again in November of that year.[73]On October 1, 1938, Skelton replaced Red Foley as the host of Avalon Time on NBC, Edna also joined the shows cast, under her maiden name.[74][l] She developed a system for working with the shows writers: selecting material from them, adding her own and filing the unused bits and lines for future use, the Skeltons worked on Avalon Time until late 1939.[76][77] Skeltons work in films led to a new regular radio show offer, between films, he promoted himself and MGM by appearing without charge at Los Angeles area banquets. A radio advertising agent was a guest at one of his banquet performances and recommended Skelton to one of his clients.[34]Skelton went on the air with his own radio show, The Raleigh Cigarette Program, on October 7, 1941. The bandleader for the show was Ozzie Nelson, his wife, Harriet, who worked under her maiden name of Hilliard, was the shows vocalist and also worked with Skelton in skits.[78]I dood it!Skelton with Doolittle Dood It newspaper headline, 1942[79]Skelton introduced the first two of his many characters during The Raleigh Cigarette Programs first season. The character of Clem Kadiddlehopper was based on a Vincennes neighbor named Carl Hopper, who was hard of hearing.[m] Skeltons voice pattern for Clem was similar to the later cartoon character, Bullwinkle, there was enough similarity to cause Skelton to contemplate filing a lawsuit against Bill Scott, who voiced the cartoon moose.[80] The second character, The Mean Widdle Kid, or Junior, was a young boy full of mischief, who typically did things he was told not to do. Junior would say things like, If I dood it, I gets a whipping., followed moments later by the statement, I dood it![80] Skelton performed the character at home with Edna, giving him the nickname Junior long before it was heard by a radio audience.[81] While the phrase was Skeltons, the idea of using the character on the radio show was Ednas.[82] Skelton starred in a 1943 movie of the same name, but did not play Junior in the film.[83]The phrase was such a part of national culture at the time that, when General Doolittle conducted the bombing of Tokyo in 1942, many newspapers used the phrase Doolittle Dood It as a headline.[34][84][85] After a talk with President Roosevelt in 1943, Skelton used his radio show to collect funds for a Douglas A-20 Havoc to be given to the Soviet Army to help fight World War II. Asking children to send in their spare change, he raised enough money for the aircraft in two weeks, he named the bomber We Dood It![86] In 1986 the Soviet newspaper Pravda offered praise to Skelton for his 1943 gift, and in 1993, the pilot of the plane was able to meet Skelton and thank him for the bomber.[87][88][n]Skelton also added a routine he had been performing since 1928. Originally called Mellow Cigars, the skit entailed an announcer who became ill as he smoked his sponsors product. Brown and Williamson, the makers of cigarettes, asked Skelton to change some aspects of the skit, he renamed the routine Guzzlers Gin, where the announcer became inebriated while sampling and touting the imaginary sponsors wares.[89] While the traditional radio program called for its cast to do an audience warm-up in preparation for the broadcast, Skelton did just the opposite. After the regular radio program had ended, the shows guests were treated to a post-program performance. He would then perform his Guzzlers Gin or any of more than 350 routines for those who had come to the radio show. He updated and revised his post-show routines as diligently as those for his radio program. As a result, studio audience tickets for Skeltons radio show were in high demand, there were times where up to 300 people needed to be turned away for lack of seats.[30][90]Divorce from Edna, marriage to GeorgiaIn 1942, Edna announced that she was leaving Skelton but would continue to manage his career and write material for him. He did not realize she was serious until Edna issued a statement about the impending divorce through NBC.[91] They were divorced in 1943, leaving the courtroom arm in arm.[92][93] The couple did not discuss the reasons for their divorce and Edna initially prepared to work as a script writer for other radio programs. When the divorce was finalized, she went to New York, leaving her former husband three fully prepared show scripts. Skelton and those associated with him sent telegrams and called her, asking her to come back to him in a professional capacity.[94][95][o] Edna remained the manager of the couples funds because Skelton spent money too easily. An attempt at managing his own checking account that began with a $5,000 balance, ended five days later after a call to Edna saying the account was overdrawn. Skelton had a weekly allowance of $75, with Edna making investments for him, choosing real estate and other relatively stable assets.[30] She remained an advisor on his career until 1952, receiving a generous weekly salary for life for her efforts.[97]The Skeltons, circa 1957. Back from left: Red, wife Georgia, sister in law Maxine Davis. Front: Son Richard and daughter ValentinaThe divorce meant that Skelton had lost his married mans deferment, he was once again classified as 1-A for service. He was drafted into the army in early 1944, both MGM and his radio sponsor tried to obtain a deferment for the comedian, but to no avail.[98] His last Raleigh radio show was on June 6, 1944, the day before he was formally inducted as a private, he was not assigned to the entertainment corps at that time. Without its star, the program was discontinued, and the opportunity presented itself for the Nelsons to begin a radio show of their own, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.[38][99]By 1944, Skelton was engaged to actress Muriel Morris, who was also known as Muriel Chase, the couple had obtained a marriage license and told the press they intended to marry within a few days. At the last minute, the actress decided not to marry him, initially saying she intended to marry a wealthy businessman in Mexico City. She later recanted the story about marrying the businessman, but continued to say that her relationship with Skelton was over. The actress further denied that the reason for the breakup was Ednas continuing to manage her ex-husbands career, Edna stated that she had no intention of either getting in the middle of the relationship or reconciling with her former husband.[100][101] He was on army furlough for throat discomfort when he married actress Georgia Maureen Davis in Beverly Hills, California, on March 9, 1945, the couple met on the MGM lot.[92][102][p] Skelton traveled to Los Angeles from the eastern army base where he was assigned for the wedding. He knew he would possibly be assigned overseas soon and wanted the marriage to take place first.[105] After the wedding, he entered the hospital to have his tonsils removed.[106][107] The couple had two children, Valentina, a daughter, was born May 5, 1947, and a son, Richard, was born May 20, 1948.[108][103][109]A cast of charactersPhoto of 1948 Raleigh Cigarette Program cast: Standing: Pat McGeehan, The Four Knights, David Rose (orchestra leader). Seated: Verna Felton (Grandma to Skeltons Junior character), Rod OConnor (announcer), Lurene Tuttle (Mother to Skeltons Junior character).[110] Front: SkeltonSkelton served in the United States Army during World War II. After being assigned to the entertainment corps, Skelton performed as many as ten to twelve shows per day before troops in both the United States and in Europe. The pressure of his workload caused him to suffer exhaustion and a nervous breakdown.[38] His nervous collapse while in the army left him with a serious stuttering problem. While recovering at an army hospital in Virginia, he met a soldier who had been severely wounded and was not expected to survive. Skelton devoted a lot of time and effort to trying to make the man laugh. As a result of this effort, his stuttering problem was cured, his army friends condition also improved and he was no longer on the critical list.[111] He was released from his army duties in September 1945.[38][112] His sponsor was eager to have him back on the air, and Skeltons program began anew on NBC on December 4, 1945.[99][113]Upon returning to radio, Skelton brought with him many new characters that were added to his repertoire: Bolivar Shagnasty, described as a loudmouthed braggart, Cauliflower McPugg, a boxer, Deadeye, a cowboy, Willie Lump-Lump, a fellow who drank too much, and San Fernando Red, a conman with political aspirations.[114] By 1947, Skeltons musical conductor was David Rose, who would go on to television with him, he had worked with Rose during his time in the army and wanted Rose to join him on the radio show when it went back on the air.[115]On April 22, 1947, Skelton was censored by NBC two minutes into his radio show. When he and his announcer Rod OConnor began talking about Fred Allen being censored the previous week, they were silenced for 15 seconds, comedian Bob Hope was given the same treatment once he began referring to the censoring of Allen.[q] Skelton forged on with his lines for his studio audiences benefit, the material he insisted on using had been edited from the script by the network before the broadcast. He had been briefly censored the previous month for the use of the word diaper. After the April incidents, NBC indicated it would no longer pull the plug for similar reasons.[117][118]Skelton changed sponsors in 1948, Brown & Williamson, owners of Raleigh cigarettes, withdrew due to program production costs. His new sponsor was Procter & Gambles Tide laundry detergent. The next year he changed networks, going from NBC to CBS, where his radio show aired until May 1953.[119][120] After his network radio contract was over, he signed a three-year contract with Ziv Radio for a syndicated radio program in 1954.[121] His syndicated radio program was offered as a daily show, it included segments of his older network radio programs as well as new material done for the syndication. He was able to use portions of his older radio shows because he owned the rights for rebroadcasting them.[71][122]Television (1951–70)Skelton was unable to work in television until the end of his 1951 MGM movie contract, a renegotiation to extend the pact provided permission after that point.[58][63] He signed a contract for television on NBC with Procter and Gamble as his sponsor on May 4, 1951, and said he would be performing the same characters on television as he had been doing on radio.[123][124] The MGM agreement with Skelton for television performances did not allow him to go on the air before September 30, 1951.[125] His television debut, The Red Skelton Show, premiered on that date: at the end of his opening monologue, two men backstage grabbed his ankles from behind the set curtain, hauling him offstage face down.[126][r] A 1943 instrumental hit by David Rose, called Holiday for Strings, became Skeltons TV theme song.[127] The move to television allowed him to create two non-human characters, seagulls Gertrude and Heathcliffe, which he performed while the pair were flying by tucking his thumbs under his arms to represent wings and shaping his hat to look like a birds bill.[128][129][130] He patterned his meek, henpecked television character of George Appleby after his radio character, J. Newton Numbskull, who had similar characteristics.[s] His Freddie the Freeloader clown was introduced on the program in 1952, with Skelton copying his fathers makeup for the character. He learned how to duplicate his fathers makeup and perform his routines through his mothers recollections.[13][132][133] A ritual became established at the end of every program, with Skeltons shy boyish wave and words of, Good night and may God bless.[134][t]Skelton as Willie Lump-Lump and Shirley Mitchell as his wife, who appears to be walking on the wall in a 1952 Skelton show sketch.During the 1951–52 season, the program was broadcast from a converted NBC radio studio.[137] The first year of the television show was done live, this led to problems as there was not enough time for costume changes, Skelton was on camera for most of the half-hour, including the delivery of a commercial which was written into one of the shows skits.[138][139] In early 1952, Skelton had an idea for a television sketch about someone who had been drinking not being able to know which way is up. The script was completed and he had the shows production crew build a set that was perpendicular to the stage, so it would give the illusion that someone was walking on walls. The skit, starring his character Willie Lump-Lump, called for the characters wife to hire a carpenter to re-do the living room in an effort to teach her husband a lesson about his drinking. When Willie wakes up there after a night of drinking, he realizes he is not lying on the floor but on the living room wall. Willies wife goes about the house normally, but to Willie, she appears to be walking on a wall. Within an hour after the broadcast, the NBC switchboard had received 350 calls regarding the show, and Skelton had received more than 2,500 letters about the skit within a week of its airing.[140]Skelton was delivering an intense performance live each week, and the strain showed in physical illness. In 1952, he was drinking heavily from the constant pain of a diaphragmatic hernia and marital problems, he thought about divorcing Georgia.[141][142][u] NBC agreed to film his shows in the 1952–53 season at Eagle Lion Studios, next to the Sam Goldwyn Studio, on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood.[145] Later the show was moved to the new NBC television studios in Burbank. Procter & Gamble was unhappy with the filming of the television show, and insisted that Skelton return to live broadcasts. The situation caused him to think about leaving television at that point.[146][147] Declining ratings prompted sponsor Procter & Gamble to cancel his show in the spring of 1953, with Skelton announcing that any future television shows of his would be variety shows, where he would not have the almost constant burden of performing.[148] Beginning with the 1953–54 season, he switched to CBS, where he remained until 1970.[149] For the initial move to CBS, he had no sponsor. The network gambled by covering all expenses for the program on a sustaining basis, his first CBS sponsor was Geritol.[150][151] He curtailed his drinking and his ratings at CBS began to improve, especially after he began appearing on Tuesday nights for co-sponsors Johnsons Wax and Pet Milk Company.[152]By 1955, Skelton was broadcasting some of his weekly programs in color, which was the case approximately 100 times between 1955 and 1960.[153] He tried to encourage CBS to do other shows in color at the facility, but CBS mostly avoided color broadcasting after the networks television set manufacturing division was discontinued in 1951.[154][v] By 1959, Skelton was the only comedian with a weekly variety television show, others who remained on the air, such as Danny Thomas, were performing their routines as part of situation comedy programs.[155][156] He performed a preview show for a studio audience on Mondays, using their reactions to determine which skits needed to be edited for the Tuesday program. For the Tuesday afternoon run-through prior to the actual show, he ignored the script for the most part, ad-libbing through it at will. The run-through was well attended by CBS Television City employees[131] Sometimes during sketches, both live telecasts and taped programs, Skelton would break up or cause his guest stars to laugh.[157][w]Richards illness and deathSkelton and Mickey Rooney at dress rehearsal for The Red Skelton Show of January 15, 1957. Skelton as a sailor and Rooney as his wife play contestants on a parody of Do You Trust Your Wife?. This was Skeltons return to television after his son Richards leukemia diagnosis.At the height of Skeltons popularity, his nine-year-old son Richard was diagnosed with leukemia and was given a year to live.[160][161] While the network told him to take as much time off as necessary, Skelton felt that until he went back to his television show, he would

Summary

Wikipedia Source: Red Skelton