Contents

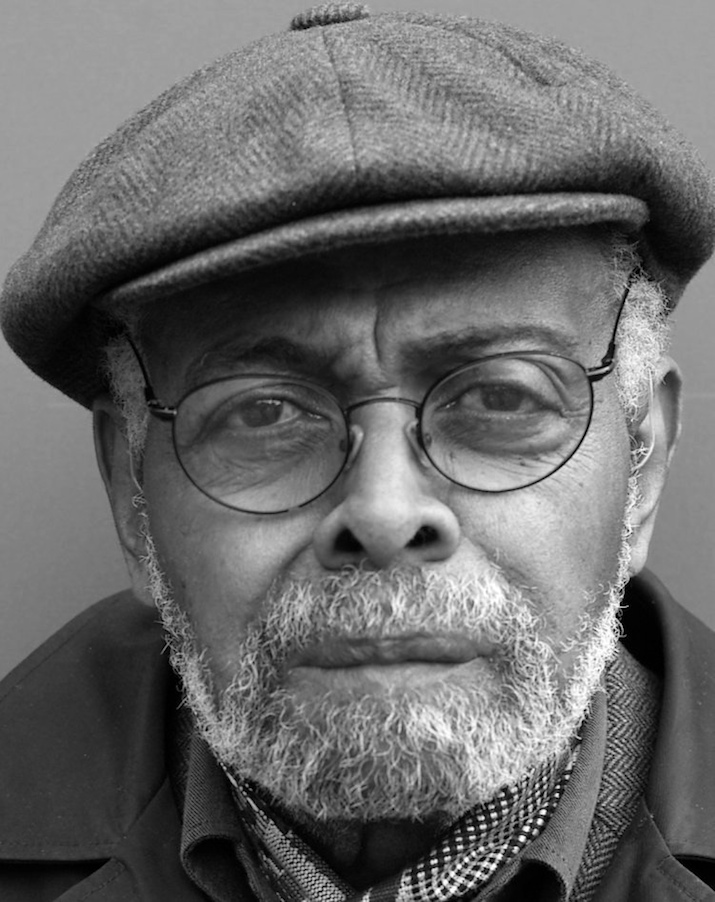

Amiri Baraka Net Worth

Everett Leroy Jones how much money? For this question we spent 15 hours on research (Wikipedia, Youtube, we read books in libraries, etc) to review the post.

The main source of income: Authors

Total Net Worth at the moment 2024 year – is about $129 Million.

Youtube

Biography

Everett Leroy Jones information Birth date: October 7, 1934, Newark, New Jersey, United States Death date: January 9, 2014, Newark, New Jersey, United States Birth place: Newark, New Jersey, USA Profession:Writer, Actor Spouse:Amina Baraka (m. 1966–2014), Hettie Jones (m. 1958–1965) Children:Ras Baraka, Lisa Jones, Kellie Jones, Shani Baraka

Height, Weight

:How tall is Amiri Baraka – 1,88m.

How much weight is Amiri Baraka – 74kg

Pictures

Wiki

Amiri Baraka (born Everett LeRoi Jones, October 7, 1934 – January 9, 2014), formerly known as LeRoi Jones and Imamu Amear Baraka, was an African-American writer of poetry, drama, fiction, essays and music criticism. He was the author of numerous books of poetry and taught at a number of universities, including the State University of New York at Buffalo and the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He received the PEN Open Book Award, formerly known as the Beyond Margins Award, in 2008 for Tales of the Out and the Gone.Baraka’s career covers nearly fifty years and his topics range from Black Liberation and White Racism. Several poems that are always associated with his name are “The Music: Reflection on Jazz and Blues,” “The Book of Monk,” and “New Music, New Poetry.” These titles draw on concepts such as society, music, and literature. Baraka', s poetry and writing have attracted both extreme praise and condemnation. Within the African-American community, some compare him to James Baldwin and call Baraka one of the most respected and most widely published Black writers of his generation. Others have said his work is an expression of violence, misogyny, homophobia and racism. Regardless of viewpoint, Baraka’s plays, poetry, and essays have been defining texts for African-American culture.Baraka', s brief tenure as Poet Laureate of New Jersey (2002–03), involved controversy over a public reading of his poem ", Somebody Blew Up America?", and accusations of anti-semitism, and some negative attention from critics, and politicians.

Biography,Early life (1934–65)Baraka was born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark, New Jersey, where he attended Barringer High School. His father, Colt Leverette Jones, worked as a postal supervisor and lift operator. His mother, Anna Lois (nee Russ), was a social worker.[14]He won a scholarship to Rutgers University in 1951, but transferred in 1952 to Howard University. His classes in philosophy and religion helped lay a foundation for his later writings. He subsequently studied at Columbia University and the New School for Social Research without obtaining a degree.In 1954, he joined the US Air Force as a gunner, reaching the rank of sergeant. His commanding officer received an anonymous letter accusing Baraka of being a communist.[15] This led to the discovery of Soviet writings in Barakas possession, his reassignment to gardening duty and subsequently a dishonorable discharge for violation of his oath of duty.[15] He later described his experience in the military as racist, degrading, and intellectually paralyzing.[16] While he was stationed in Puerto Rico, he worked at the base library, which allowed him ample reading time, and it was here that, inspired by Beat poets back in America, he began to write poetry.The same year, he moved to Greenwich Village, working initially in a warehouse of music records. His interest in jazz began during this period. At the same time he came in contact with the avant-garde Black Mountain poets and New York School poets. In 1958 he married Hettie Cohen, with whom he had two daughters, Kellie Jones (b. 1959) and Lisa Jones (b.1961). He and Hettie founded Totem Press, which published such Beat poets as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.[17] They also jointly founded a quarterly literary magazine, Yugen, which ran for eight issues (1958–62).[18]Baraka also worked as editor and critic for the literary and arts journal Kulchur (1960–65). With Diane di Prima he edited the first twenty-five issues (1961–63) of their little magazine The Floating Bear.[11] In the autumn of 1961 he co-founded the New York Poets Theatre with di Prima, the choreographers Fred Herko and James Waring, and the actor Alan S. Marlowe. He had an extramarital affair with di Prima for several years, their daughter, Dominique di Prima, was born in June 1962.Baraka visited Cuba in July 1960 with a Fair Play for Cuba Committee delegation and reported his impressions in his essay Cuba Libre.[19] There he encountered openly rebellious artists who declared him to be a cowardly bourgeois individualist[20] more focused on building his reputation than trying to help those who were enduring oppression. This encounter caused a dramatic change in his writing and goals, causing him to become emphatic about supporting black nationalism.In 1961 Baraka co-authored a Declaration of Conscience in support of Fidel Castros regime.[21] Baraka also was a member of the Umbra Poets Workshop of emerging Black Nationalist writers (Ishmael Reed and Lorenzo Thomas among others) on the Lower East Side (1962–65).His first book of poems, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, was published in 1961. Barakas article The Myth of a Negro Literature (1962) stated that a Negro literature, to be a legitimate product of the Negro experience in America, must get at that experience in exactly the terms America has proposed for it in its most ruthless identity. He also stated in the same work that as an element of American culture, the Negro was entirely misunderstood by Americans. The reason for this misunderstanding and for the lack of black literature of merit was, according to Jones:“In most cases the Negroes who found themselves in a position to pursue some art, especially the art of literature, have been members of the Negro middle class, a group that has always gone out of its way to cultivate any mediocrity, as long as that mediocrity was guaranteed to prove to America, and recently to the world at large, that they were not really who they were, i.e., Negroes.”As long as black writers were obsessed with being an accepted middle class, Baraka wrote, they would never be able to speak their mind, and that would always lead to failure. Baraka felt that America only made room for white obfuscators, not black ones.[22][23]In 1963 Baraka (under the name LeRoi Jones) published Blues People: Negro Music in White America, his account of the development of black music from slavery to contemporary jazz.[24] When the work was re-issued in 1999, Baraka wrote in the Introduction that he wished to show that The music was the score, the actually expressed creative orchestration, reflection of Afro-American life…. That the music was explaining the history as the history was explaining the music. And that both were expressions of and reflections of the people.[25] He argued that though the slaves had brought their musical traditions from Africa, the blues were an expression of what black people became in America: The way I have come to think about it, blues could not exist if the African captives had not become American captives.[26]Baraka (under the name LeRoi Jones) wrote an acclaimed, controversial play Dutchman, in which a white woman accosts a black man on the New York subway. The play premiered in 1964 and received the Obie Award for Best American Play in the same year.[27] A film of the play, directed by Anthony Harvey, was released in 1967.[28] The play has been revived several times, including a 2013 production staged in the Russian and Turkish Bathhouse in the East Village, Manhattan.[29]After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Baraka left his wife and their two children and moved to Harlem, where he founded the Black Arts Repertory/Theater School since the Black Arts Movement created a new visual representation of art. He moved back to Newark after allegations surfaced that he was using federal antipoverty welfare funds for his theater.[30]Baraka became a leading advocate and theorist for the burgeoning black art during this time.[24] Now a black cultural nationalist, he broke away from the predominantly white Beats and became critical of the pacifist and integrationist Civil Rights movement. His revolutionary poetry became more controversial.[11] A poem such as Black Art (1965), according to Werner Sollors, of Harvard University, expressed his need to commit the violence required to establish a Black World.[31]Baraka even uses onomatopoeia in Black Art to express that need for violence: rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr . . . tuhtuhtuhtuhtuhtuht . . . More specifically, lines in Black Art such as Let there be no love poems written / until love can exist freely and cleanly juxtaposed with We want a black poem. / And a Black World demonstrate Barakas cry for political justice during a time when racial injustice was rampant, despite the Civil Rights Movement.[32]Black Art quickly became the major poetic manifesto of the Black Arts Literary Movement and in it, Jones declaimed, we want poems that kill, which coincided with the rise of armed self-defense and slogans such as Arm yourself or harm yourself that promoted confrontation with the white power structure. Rather than use poetry as an escapist mechanism, Baraka saw poetry as a weapon of action.[33] His poetry demanded violence against those he felt were responsible for an unjust society.Baraka also promoted theatre as a training for the real revolution yet to come, with the arts being a way to forecast the future as he saw it. In The Revolutionary Theatre, Baraka wrote, We will scream and cry, murder, run through the streets in agony, if it means some soul will be moved. [34] In opposition to the peaceful protests inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., Baraka believed that a physical uprising must follow the literary one.1966–80In 1966, Baraka married his second wife, Sylvia Robinson, who later adopted the name Amina Baraka.[35] The two would open a facility in Newark known as Spirit House, a combination playhouse and artists’ residence.[30] In 1967, he lectured at San Francisco State University. The year after, he was arrested in Newark for having allegedly carried an illegal weapon and resisting arrest during the 1967 Newark riots, and was subsequently sentenced to three years in prison. His poem Black People, published in the Evergreen Review of December 1967, was read by the judge in court,[36] including the memorable phrase: All the stores will open if you say the magic words. The magic words are: Up against the wall motherfucker this is a stick up![37] Shortly afterward an appeals court reversed the sentence based on his defense by attorney Raymond A. Brown.[38] He later joked that he was charged with holding two revolvers and two poems.[34]Not long after the 1967 riots, Baraka generated controversy when he went on the radio with a Newark police captain and Anthony Imperiale, a politician and private business owner, and the three of them blamed the riots on white-led, so-called radical groups and Communists and the Trotskyite persons.[39] That same year his second book of jazz criticism, Black Music, came out, a collection of previously published music journalism, including the seminal Apple Cores columns from Down Beat magazine. Around this time he also formed a record label called Jihad, which produced and issued only three LPs, all released in 1968:[40] Sonnys Time Now with Sunny Murray, Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Louis Worrell, Henry Grimes, and Baraka, A Black Mass, featuring Sun Ra, and Black & Beautiful – Soul & Madness by the Spirit House Movers, on which Baraka reads his poetry.[41][42]In 1967, Baraka (still Leroi Jones) visited Maulana Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of his philosophy of Kawaida, a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy that produced the Nguzo Saba, Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names. It was at this time that he adopted the name Imamu Amear Baraka. Imamu is a Swahili title for spiritual leader, derived from the Arabic word Imam (????). According to Shaw, he dropped the honorific Imamu and eventually changed Amear (which means Prince) to Amiri. Baraka means blessing, in the sense of divine favor.In 1970 he strongly supported Kenneth A. Gibsons candidacy for mayor of Newark, Gibson was elected the citys first Afro-American Mayor.In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Baraka courted controversy by penning some strongly anti-Jewish poems and articles, similar to the stance at that time of the Nation of Islam. Historian Melani McAlister points to an example of this writing In the case of Baraka, and in many of the pronouncements of the NOI [Nation of Islam], there is a profound difference, both qualitative and quantitative, in the ways that white ethnicities were targeted. For example, in one well-known poem, Black Arts [originally published in The Liberator January 1966], Baraka made offhand remarks about several groups, commenting in the violent rhetoric that was often typical of him, that ideal poems would knockoff … dope selling wops and suggesting that cops should be killed and have their tongues pulled out and sent to Ireland. But as Baraka himself later admitted [in his piece I was an AntiSemite published by The Village Voice on December 20, 1980 vol 1], he held a specific animosity for Jews, as was apparent in the different intensity and viciousness of his call in the same poem for dagger poems to stab the slimy bellies of the ownerjews and for poems that crack steel knuckles in a jewladys mouth.[43]Prior to this time, Baraka prided himself on being a forceful advocate of black cultural nationalism, however, by the mid-1970s, he began finding its racial individuality confining.[11] Barakas separation from the Black Arts Movement began because he saw certain black writers – capitulationists, as he called them – countering the Black Arts Movement that he created. He believed that the groundbreakers in the Black Arts Movement were doing something that was new, needed, useful, and black, and those who did not want to see a promotion of black expression were appointed to the scene to damage the movement.[22]Around 1974, Baraka distanced himself from Black nationalism and became a Marxist and a supporter of third-world liberation movements.In 1979 he became a lecturer in the State University of New York at Stony Brooks Africana Studies Department in the College of Arts and Sciences due to the urging of faculty member Leslie Owens. Articles about Baraka appeared in the Universitys print media from Stony Brook Press, Blackworld, and other student campus publications. These articles included an expose about his positions on page one of the inaugural issue of Stony Brook Press on October 25, 1979 discussing his protests against what he perceived as racism in the Africana Studies Department, as evidenced by a dearth of tenured professors. Baraka was later hired as an assistant professor at Stony Brook to assist the struggling Africana Studies Department.[44]In June 1979 Baraka was arrested and jailed at Eighth Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Different accounts emerged around the arrest, all sides agree that Baraka and his wife, Amina, were in their car arguing over the cost of their childrens shoes. The police version of events holds that they were called to the scene after a report of an assault in progress. They maintain that Baraka was striking his wife and when they moved to intervene he attacked them as well, whereupon they used the necessary force to subdue him. Aminas account contrasted with that of the police, she held a news conference the day after the arrest accusing the police of lying. A grand jury dismissed the assault charge but the resisting arrest charge moved forward.[45] In November 1979 after a seven-day trail a Criminal Court jury found Baraka guilty of resisting arrest. A month later he was sentenced to 90 days at Rikers Island (the maximum he could have been sentenced to was one year). Amina declared that her husband was a political prisoner. Baraka was released after a day in custody pending his appeal. At the time it was noted if he was kept in prison he would be unable to attend a reception at the White House in honor of American poets. Barakas appeal continued up to the State Supreme Court. During the process his lawyer William M. Kunstler told the press Baraka feels its the responsibility of the writers of America to support him across the board. Backing for his attempts to have the sentence cancelled or reduced came from letters of support from elected officials, artists and teachers around the country.[45] Amina Baraka continued to advocate for her husband and at one press conference stated Fascism is coming and soon the secret police will shoot our children down in the streets.[46] In December 1981 Judge Benrard Fried ruled against Baraka and ordered him to report to Rikers Island to serve his sentence on weekends occurring between January 9, 1982 through November 6, 1982. The judge noted that by having Baraka serve his 90 days on weekends this would allow him to continue his teaching obligations at Stony Brook.[47] Rather than serve his sentence at the prison Baraka was allowed to serve his 48 consecutive weekends in a Harlem halfway house. While serving his sentence he wrote The AutoBiography, tracing his life from birth to his conversion to socialism.[48]1980–2014In 1980 Baraka published an essay in the Village Voice that was titled Confessions of a Former Anti-Semite. Baraka insisted that a Village Voice editor entitled it and not himself. In the essay Baraka went over his life history including his marriage to Hettie Cohen who was of Jewish descent. He stated that after the assassination of Malcolm X he found himself thinking As a Black man married to a white woman, I began to feel estranged from her … How could someone be married to the enemy? So he divorced Hettie and left her with their two bi-racial daughters. In the essay Baraka went on to say We also know that much of the vaunted Jewish support of Black civil rights organizations was in order to use them. Jews, finally, are white, and suffer from the same kind of white chauvinism that separates a great many whites from Black struggle. …these Jewish intellectuals have been able to pass over the into the Promised Land of American privilege. In the essay he also defended his position against Israel saying Zionism is a form of racism. Near the end of the essay Baraka stated Anti-Semitism is as ugly an idea and as deadly as white racism and Zionism …As for my personal trek through the wasteland of anti-Semitism, it was momentary and never completely real. …I have written only one poem that has definite aspects of anti-Semitism…and I have repudiated it as thoroughly as I can.[49] The poem Baraka referenced was For Tom Postell, Dead Black Poet which contained lines including …Smile jew. Dance, jew. Tell me you love me, jew. I got something for you… I got the extermination blues, jewboys. I got the hitler syndrome figured…So come for the rent, jewboys…one day, jewboys, we all, even my wig wearing mother gonna put it on you all at once.[49]Baraka addressing the Malcolm X Festival from the Black Dot Stage in San Antonio Park, Oakland, California while performing with Marcel Diallo and his Electric Church BandDuring the 1982–83 academic year, Baraka was a visiting professor at Columbia University, where he taught a course entitled Black Women and Their Fictions. In 1984 he became a full professor at Rutgers University, but was subsequently denied tenure.[50] In 1985, Baraka returned to Stony Brook, eventually becoming professor emeritus of African Studies. In 1987, together with Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, he was a speaker at the commemoration ceremony for James Baldwin.In 1989 Baraka won an American Book Award for his works as well as a Langston Hughes Award. In 1990 he co-authored the autoBiography, of Quincy Jones, and 1998 was a supporting actor in Warren Beattys film Bulworth. In 1996, Baraka contributed to the AIDS benefit album Offbeat: A Red Hot Soundtrip produced by the Red Hot Organization.In July 2002, Baraka was named Poet Laureate of New Jersey by Governor Jim McGreevey. The position was to be for two years and came with a $10,000 stipend.[51] Baraka held the post for a year mired in controversy and after substantial political pressure and public outrage demanding his resignation. During the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival in Stanhope, New Jersey, Baraka read his 2001 poem on the September 11th attacks Somebody Blew Up America?, which was criticized for anti-Semitism and attacks on public figures. Because there was no mechanism in the law to remove Baraka from the post, the position of state poet laureate was officially abolished by the State Legislature and Governor McGreevey.[52]Baraka collaborated with hip-hop group The Roots on the song Something in the Way of Things (In Town) on their 2002 album Phrenology.In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Amiri Baraka on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[53]In 2003, Barakas daughter Shani, aged 31, and her lesbian partner, Rayshon Homes, were murdered in the home of Shanis sister, Wanda Wilson Pasha, by Pashas ex-husband, James Coleman.[54][55] Prosecutors argued that Coleman shot Shani because she had helped her sister separate from her husband.[56] A New Jersey jury found Coleman (also known as Ibn El-Amin Pasha) guilty of murdering Shani Baraka and Rayshon Holmes, and he was sentenced to 168 years in prison for the 2003 shooting.[57]His son, Ras J. Baraka (born 1970), is a politician and activist in Newark, who served as principal of Newarks Central High School, as an elected member of the Municipal Council of Newark (2002–06, 2010–present) representing the South Ward. Ras J. Baraka became Mayor of Newark, July 1, 2014. See 2014 Newark mayoral election.DeathAmiri Baraka died on January 9, 2014, at Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, New Jersey, after being hospitalized in the facilitys intensive care unit for one month prior to his death. The cause of death was not reported initially, but it is mentioned that Baraka had a long struggle with diabetes.[58] Later reports indicated that he died from complications after a recent surgery.[59] Barakas funeral was held at Newark Symphony Hall on January 18, 2014.[60]

Summary

Wikipedia Source: Amiri Baraka