Contents

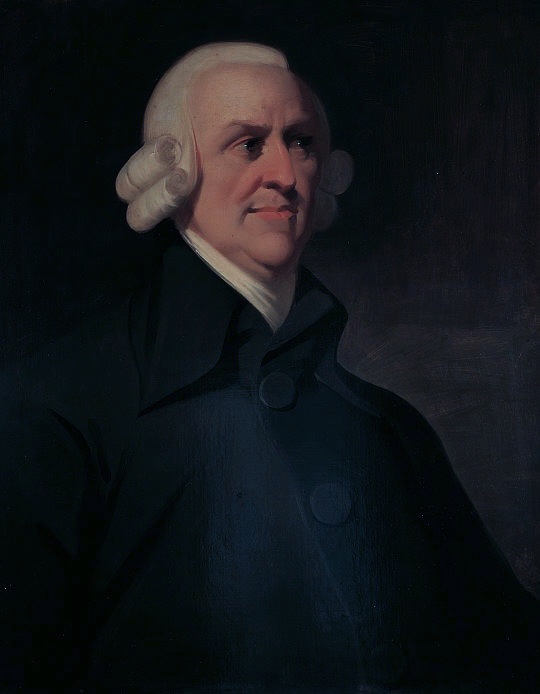

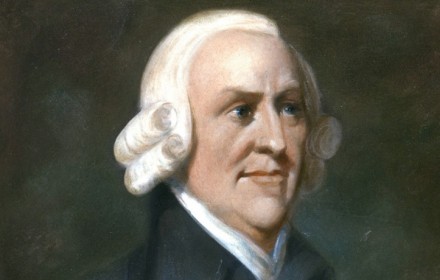

Adam Smith Net Worth

How Much money Adam Smith has? For this question we spent 14 hours on research (Wikipedia, Youtube, we read books in libraries, etc) to review the post.

The main source of income: Celebrities

Total Net Worth at the moment 2024 year – is about $73,8 Million.

Youtube

Biography

Adam Smith information Birth date: 0001-06-05 Death date: 1790-07-17 Birth place: Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland Profession:Editorial Department, Animation Department, Editor Nationality:Scottish

Height, Weight:

How tall is Adam Smith – 1,67m.

How much weight is Adam Smith – 60kg

Pictures

Wiki

Biography,Early lifePortrait of Smiths mother, Margaret DouglasSmith was born in Kirkcaldy, in the County of Fife, Scotland. His father, also Adam Smith, was a Scottish Writer to the Signet (senior solicitor), advocate, and prosecutor (Judge Advocate) and also served as comptroller of the Customs in Kirkcaldy. In 1720 he married Margaret Douglas, daughter of the landed Robert Douglas of Strathendry, also in Fife. His father died two months after he was born, leaving his mother a widow. The date of Smiths baptism into the Church of Scotland at Kirkcaldy was 5 June 1723, and this has often been treated as if it were also his date of birth, which is unknown. Although few events in Smiths early childhood are known, the Scottish journalist John Rae, Smiths biographer, recorded that Smith was abducted by gypsies at the age of three and released when others went to rescue him.[N 1] Smith was close to his mother, who probably encouraged him to pursue his scholarly ambitions. He attended the Burgh School of Kirkcaldy—characterised by Rae as one of the best secondary schools of Scotland at that period—from 1729 to 1737, he learned Latin, mathematics, history, and writing.Formal educationA commemorative plaque for Smith is located in Smiths home town of Kirkcaldy.Smith entered the University of Glasgow when he was fourteen and studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson. Here, Smith developed his passion for liberty, reason, and free speech. In 1740 Smith was the graduate scholar presented to undertake postgraduate studies at Balliol College, Oxford, under the Snell Exhibition.[11]Adam Smith considered the teaching at Glasgow to be far superior to that at Oxford, which he found intellectually stifling.[12] In Book V, Chapter II of The Wealth of Nations, Smith wrote: In the University of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching. Smith is also reported to have complained to friends that Oxford officials once discovered him reading a copy of David Humes Treatise on Human Nature, and they subsequently confiscated his book and punished him severely for reading it.[13][14] According to William Robert Scott, The Oxford of [Smiths] time gave little if any help towards what was to be his lifework.[15] Nevertheless, Smith took the opportunity while at Oxford to teach himself several subjects by reading many books from the shelves of the large Bodleian Library.[16] When Smith was not studying on his own, his time at Oxford was not a happy one, according to his letters.[17] Near the end of his time there, Smith began suffering from shaking fits, probably the symptoms of a nervous breakdown.[18] He left Oxford University in 1746, before his scholarship ended.[18][19]In Book V of The Wealth of Nations, Smith comments on the low quality of instruction and the meager intellectual activity at English universities, when compared to their Scottish counterparts. He attributes this both to the rich endowments of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, which made the income of professors independent of their ability to attract students, and to the fact that distinguished men of letters could make an even more comfortable living as ministers of the Church of England.[14]Adam Smiths discontent at Oxford might be in part due to the absence of his beloved teacher in Glasgow, Francis Hutcheson. Hutcheson was well regarded as one of the most prominent lecturers at the University of Glasgow in his day and earned the approbation of students, colleagues, and even ordinary residents with the fervor and earnestness of his orations (which he sometimes opened to the public). His lectures endeavoured not merely to teach philosophy but to make his students embody that philosophy in their lives, appropriately acquiring the epithet, the preacher of philosophy. Unlike Smith, Hutcheson was not a system builder, rather it was his magnetic personality and method of lecturing that so influenced his students and caused the greatest of those to reverentially refer to him as the never to be forgotten Hutcheson—a title that Smith in all his correspondence used to describe only two people, his good friend David Hume and influential mentor Francis Hutcheson.[20]Teaching careerSmith began delivering public lectures in 1748 in Edinburgh, sponsored by the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames.[21] His lecture topics included rhetoric and belles-lettres,[22] and later the subject of the progress of opulence. On this latter topic he first expounded his economic philosophy of the obvious and simple system of natural liberty. While Smith was not adept at public speaking, his lectures met with success.[23]David Hume was a friend and contemporary of Smith.In 1750, he met the philosopher David Hume, who was his senior by more than a decade. In their writings covering history, politics, philosophy, economics, and religion, Smith and Hume shared closer intellectual and personal bonds than with other important figures of the Scottish Enlightenment.[24]In 1751, Smith earned a professorship at Glasgow University teaching logic courses, and in 1752 he was elected a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, having been introduced to the society by Lord Kames. When the head of Moral Philosophy in Glasgow died the next year, Smith took over the position.[23] He worked as an academic for the next thirteen years, which he characterised as by far the most useful and therefore by far the happiest and most honorable period [of his life].[25]Smith published The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, embodying some of his Glasgow lectures. This work was concerned with how human morality depends on sympathy between agent and spectator, or the individual and other members of society. Smith defined mutual sympathy as the basis of moral sentiments. He based his explanation, not on a special moral sense as the Third Lord Shaftesbury and Hutcheson had done, nor on utility as Hume did, but on mutual sympathy, a term best captured in modern parlance by the twentieth-century concept of empathy, the capacity to recognise feelings that are being experienced by another being.Following the publication of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith became so popular that many wealthy students left their schools in other countries to enroll at Glasgow to learn under Smith.[26] After the publication of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith began to give more attention to jurisprudence and economics in his lectures and less to his theories of morals.[27] For example, Smith lectured that the cause of increase in national wealth is labour, rather than the nations quantity of gold or silver, which is the basis for mercantilism, the economic theory that dominated Western European economic policies at the time.[28]Francois Quesnay, one of the leaders of the Physiocratic school of thoughtIn 1762, the University of Glasgow conferred on Smith the title of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.). At the end of 1763, he obtained an offer from Charles Townshend—who had been introduced to Smith by David Hume—to tutor his stepson, Henry Scott, the young Duke of Buccleuch. Smith then resigned from his professorship to take the tutoring position. He subsequently attempted to return the fees he had collected from his students because he resigned in the middle of the term, but his students refused.[29]Tutoring and travelsSmiths tutoring job entailed touring Europe with Scott, during which time he educated Scott on a variety of subjects—such as proper Polish.[29] He was paid ?300 per year (plus expenses) along with a ?300 per year pension, roughly twice his former income as a teacher.[29] Smith first travelled as a tutor to Toulouse, France, where he stayed for one and a half years.[29] According to his own account, he found Toulouse to be somewhat boring, having written to Hume that he had begun to write a book to pass away the time.[29] After touring the south of France, the group moved to Geneva, where Smith met with the philosopher Voltaire.[30]From Geneva, the party moved to Paris. Here Smith came to know several great intellectual leaders of the time, invariably having an effect on his future works. This list included: Benjamin Franklin,[31] Turgot, Jean DAlembert, Andre Morellet, Helvetius, and, notably, Francois Quesnay, the head of the Physiocratic school.[32] So impressed with his ideas[33] Smith considered dedicating The Wealth of Nations to him had Quesnay not died beforehand.[34] Physiocrats were opposed to mercantilism, the dominating economic theory of the time. Illustrated in their motto Laissez faire et laissez passer, le monde va de lui meme! (Let do and let pass, the world goes on by itself!). They were also known to have declared that only agricultural activity produced real wealth, merchants and industrialists (manufacturers) did not.[31] This however, did not represent their true school of thought, but was a mere smoke screen manufactured to hide their actual criticisms of the nobility and church, arguing that they made up the only real clients of merchants.[35]The wealth of France was virtually destroyed by Louis XIV and Louis XV in ruinous wars,[36] by aiding the American insurgents against the British, and perhaps most destructive (in terms of public perceptions) was what was seen as the excessive consumption of goods and services deemed to have no economic contribution—unproductive labour. Assuming that nobility and church are essentially detractors from economic growth, the feudal system of agriculture in France was the only sector important to maintain the wealth of the nation. Given that the English economy of the day yielded an income distribution that stood in contrast to that which existed in France, Smith concluded that the teachings and beliefs of Physiocrats were, with all [their] imperfections [perhaps], the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy.[37] The distinction between productive versus unproductive labour—the physiocratic classe steril—was a predominant issue in the development and understanding of what would become classical economic theory.Later yearsIn 1766, Henry Scotts younger brother died in Paris, and Smiths tour as a tutor ended shortly thereafter.[31] Smith returned home that year to Kirkcaldy, and he devoted much of the next ten years to his magnum opus.[38] There he befriended Henry Moyes, a young blind man who showed precocious aptitude. As well as teaching Moyes, Smith secured the patronage of David Hume and Thomas Reid in the young mans education.[39] In May 1773, Smith was elected fellow of the Royal Society of London,[40] and was elected a member of the Literary Club in 1775.[41] The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776 and was an instant success, selling out its first edition in only six months.[42]In 1778, Smith was appointed to a post as commissioner of customs in Scotland and went to live with his mother in Panmure House in Edinburghs Canongate.[43] Five years later, as a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh when it received its royal charter, he automatically became one of the founding members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,[44] and from 1787 to 1789 he occupied the honorary position of Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow.[45] He died in the northern wing of Panmure House in Edinburgh on 17 July 1790 after a painful illness and was buried in the Canongate Kirkyard.[46] On his death bed, Smith expressed disappointment that he had not achieved more.[47]Smiths literary executors were two friends from the Scottish academic world: the physicist and chemist Joseph Black, and the pioneering geologist James Hutton.[48] Smith left behind many notes and some unpublished material, but gave instructions to destroy anything that was not fit for publication.[49] He mentioned an early unpublished History of Astronomy as probably suitable, and it duly appeared in 1795, along with other material such as Essays on Philosophical Subjects.[48]Smiths library went by his will to David Douglas, Lord Reston (son of his cousin Colonel Robert Douglas of Strathendry, Fife), who lived with Smith. It was eventually divided between his two surviving children, Cecilia Margaret (Mrs. Cunningham) and David Anne (Mrs. Bannerman). On the death of her husband, the Rev. W. B. Cunningham of Prestonpans in 1878, Mrs. Cunningham sold some of the books. The remainder passed to her son, Professor Robert Oliver Cunningham of Queens College, Belfast, who presented a part to the library of Queens College. After his death the remaining books were sold. On the death of Mrs. Bannerman in 1879 her portion of the library went intact to the New College (of the Free Church), Edinburgh.

Summary

Wikipedia Source: Adam Smith